HRW urged Bangladesh heeding UN recommendations on torture

- Nayadiganta English Desk

- 30 July 2019, 08:28

Human Rights Watch (HRW) on Monday urged Bangladesh to implement the recommendations made by the United Nations Committee against Torture to end the widespread practice of torture in the country.

The committee’s first review of Bangladesh under the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment will be from July 29 to August 8, 2019, in Geneva.

Bangladeshi security forces are seldom held accountable for serious allegations of torture and other ill-treatment of people in custody. Instead, authorities have cracked down on rights groups, activists, and journalists for exposing these violations.

Bangladesh, for the first time, agreed to come under review by the committee since ratifying the Convention against Torture over 20 years ago, by submitting its long-overdue state report on measures it has taken to uphold its commitments under the treaty.

The government claimed that it “has already undertaken several measures to improve the responses from the authorities and bodies responsible for promotion and protection of human rights and also the quality of access to justice for the victims of torture.”

“Bangladesh’s appearance before the UN Committee Against Torture is an important opportunity to acknowledge the endemic use of torture by the country’s security forces,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch.

He added: “The government should adopt the committee’s recommendations, enforce existing laws against torture, and send a clear message to security forces that it’s serious about eradicating torture.”

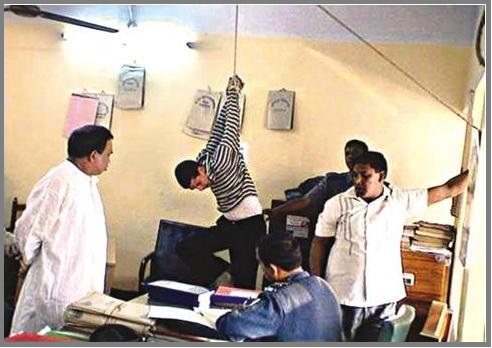

Human Rights Watch has documented widespread torture by Bangladesh security forces including beating detainees with iron rods, belts, and sticks; subjecting detainees to electric shocks, waterboarding, hanging detainees from ceilings and beating them; and deliberately shooting detainees, typically in the lower leg, described as “kneecapping.” Authorities routinely claim that these victims were shot in self-defense, in “crossfire,” or during violent protests.

In 2013, the government passed the Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention) Act, signaling a commitment to eliminating torture. However, there have been very few cases filed under the Torture Act and not a single case has been completed.

Meanwhile, investigations by human rights organizations suggest that authorities still routinely torture people in custody. Since the passage of the law, there have been 160 documented cases of torture. The actual number is likely much higher.

Instead of enforcing the law, Bangladeshi police have repeatedly called for the government to amend it to be less prohibitive, calling into question whether Bangladesh’s security forces are serious about ending their torture practices.

In 2015, the police submitted a proposal to the Ministry of Home Affairs to repeal section 12 of the Torture Act, which states that circumstances such as war, political instability, or emergency are not considered an acceptable excuse for the commission of torture.

They also proposed that certain law enforcement units – including those with the most notorious reputations for committing torture, such as the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), the Criminal Investigations Department, the Special Branch, and the Detective Branch – be excluded from prosecution under the act.

Last year, during Bangladesh Police Week 2018, the police again implored Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to amend the act, and Hasina said she would consider it, according to the Dhaka Tribune.

Instead of succumbing to police pressure, the government should stand firm behind its international commitments to eradicate torture, Human Rights Watch said.

In its report submitted to the Committee against Torture, Bangladesh outlined its commitments under domestic and international law to protect against forced confessions, including that a magistrate must explain to the accused that they are “not bound to make a confession, and that if he does so it may be used as evidence against him. Moreover, a Magistrate should not record any such confession unless he has reason to believe that it is being made voluntarily.”

However, Human Rights Watch has documented numerous reports of RAB, the Director General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), and the police using torture to extract confessions, often making suspects sign blank sheets of paper.

Sections 54 and 167 of the Criminal Procedure Code empower the police to detain people for 15 days without a lawyer, known as remand, which has long been criticized as a loophole for torture. Human rights organizations have repeatedly documented that instances of torture most frequently occur during remand.

In 2003, the High Court Division of Bangladesh concluded that, deployed broadly, sections 54 and 167 were inconsistent with rights guaranteed in the constitution.

The Supreme Court issued 15 directives to safeguard against abuse of the powers of arrest and interrogation in custodial detention, including that authorities must take permission from a magistrate to conduct interrogation in remand and that it must take place in a room with glass walls inside the prison, with lawyers and relatives allowed to monitor nearby.

Moreover, authorities must inform the person of the reason for arrest within three hours and ensure that a relative or friend of the detained person is informed within 12 hours of the arrest about the time, place of arrest, and place of detention.

But these directives are inconsistently followed, if at all, Human Rights Watch said. Since 2013 – the same year the Torture Act passed – arbitrary detention and enforced disappearances by law enforcement authorities have increased.

In most cases, those arrested remain in custody for weeks or months before being formally charged or released. Others are killed in so-called armed exchanges, and many remain disappeared.

There were 90 reported cases of disappearances in 2018 alone. While many of those disappeared are never located or released, those who are, often are afraid to speak out. However, those who do describe their experiences consistently allege severe torture.

For example, Idris Ali, 56, a leader of Jamaat-e-Islami, Bangladesh’s largest Islamist party, was on his motorbike returning to his house from the market on August 4, 2016, when, according to witnesses, plainclothes people from a police post stopped him and forcibly dragged him away.

Family members went to their local police station but the officer-in-charge told them that the location where Ali was allegedly taken was not within the station’s jurisdiction, and that they should go to the Shailkupa police station to file a report.

Officers there, however, declined to allow them to do so. On the morning of August 12, police informed the family that the body of a missing madrasa teacher was found on the Harinakundu-Jhenaidah road. A family member said they went to the morgue:

We went there and found his mutilated body. After conducting autopsy and postmortem examinations, police claimed that it was a case of a road mishap, and Idris’s motorcycle was found at the roadside. We, however, identified marks of severe torture on different parts of the body.

There were marks of hammering behind the head. Tendons were slashed. All the parts of the body bore torture marks.

In other cases, families still wait for answers with authorities denying the arrests, although in several cases, there are credible witnesses that say that their relatives were taken into custody by security forces.

“Bangladesh should be commended for committing to work with the UN to fulfill its mandate to prevent torture,” Adams said. “But the government needs to recognize and take responsibility for the torture committed by its security forces today.”

Kamruzzaman

More News

-

- ৫ঃ ৪০

- খেলা

-

- ৫ঃ ৪০

- খেলা